Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

Sydney Theatre Company, His Majesty's Theatre, Perth Festival

Reviewed by Wolfgang von Flüglehorn

I felt especially fortunate to be seeing Kip Williams’s dazzling adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Doctor Jekyll and Mr Hyde in Perth framed by the Edwardian grandeur of His Majesty’s Theatre, with its sumptuous blood-red carpets, curtains, seats and walls, and its beautifully restored ambience haunted by theatre ghosts.

In fact the production could hardly have been put on elsewhere in the city because of the vast space required in terms of the dimensions of the stage – initially almost bare apart from a diagonal line of streetlamps and a continuous drift of stage fog – not to mention the capacious wings and especially the fly-tower.

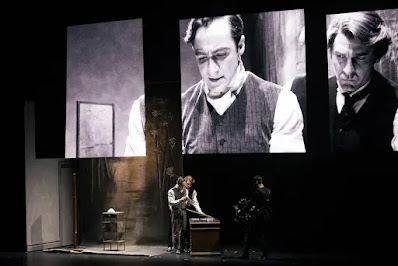

Inside the frame of the proscenium arch, two actors – Ewen Leslie and Matthew Backer – play Hyde and Seek in an ever-changing hall of mirrors. Adaptor-director Williams’s self-described hybrid form of ‘cine-theatre’ is a kind of infernal machine with continuously moving parts.

Huge flats rapidly descend and reascend from the flies to serve as projection screens, displaying a seamless mix of live-feed and pre-edited video footage with which the two actors (equally seamlessly) interact; in a more traditionally theatrical way, the flats also provide temporary screens for them to hide behind for the purpose of quick costume changes.

Meanwhile a crack team of technical and stage crew hurtle around the stage with Steadicams or scenery on wheels including building facades, doors, rooms, inner walls and staircases, as well as props and costumes like tables, chairs, portraits, looking-glasses, glasses of wine, writing materials, laboratory equipment, walking sticks, hats, coats, wigs and facial hair.

This Heath-Robinson-like assemblage reflects the convoluted structure of Stevenson’s novella, with its nested stories, time jumps, plot twists and continual changes in narrative form and perspective; its enigmatic urban geography, maze-like streets and puzzling architecture; its locked doors, desk drawers and safety-deposit boxes; and its sealed envelopes-within-envelopes containing legal documents and letters.

Williams’s previous adaptation of Wilde’s similarly Victorian Gothic novel The Picture of Dorian Gray (which I reviewed in an earlier blog post when it was at the Adelaide Festival last year) used screen technology to present a brilliantly superficial world of simulation and hypervisibility. Jekyll and Hyde employs the same devices to investigate a darker realm of dissimulation and concealment (as the name ‘Hyde’ suggests). In both cases the Victorian preoccupation with thresholds and portals – mysterious doors, portraits, potions, looking-glasses, rabbit holes – leads us into a labyrinth from which there is no escape.

If Eryn-Jean Norvill’s solo portrayal of all the characters in Dorian Gray gleefully (if tragically) emphasized that novel’s underlying theme of narcissism, then Backer and Leslie’s hand-in-glove double-act in Jekyll and Hyde evokes the typically Victorian Gothic figure of the doppelganger. The effect is heightened by the fact that the two actors physically resemble each other onstage; it’s reinforced by the use of costume as a form of disguise; as well as the blocking, where they frequently mirror each other; and the screens, where they’re reduplicated by multiple versions of themselves (and in the case of Leslie sometimes play multiple characters simultaneously).

Backer plays Jekyll’s taciturn but tolerant lawyer-friend and confidante Utterson; the name is also surely a joke, as he listens but rarely speaks to Jekyll, while maintaining the role of protagonist and narrator-in chief to the audience. He also becomes a prototypical detective in the ‘strange case’ that unfolds. Meanwhile Leslie plays Jekyll and Hyde as well as all the other characters in an astonishing tour-de-force of virtuosity and sustained intensity.

As far as I could tell, the text seemed remarkably faithful to the words of the original; Williams’s edits or interpolations were as difficult to detect as the transitions from live to pre-edited footage. The most significant departure from the novella – and the turning point of the show – occurs in the final section when Utterson reads Jekyll’s confession and ‘full statement of the case’. At this point both actors repeatedly drink the transformative potion, while the soundtrack transitions from a Bernard Hermann-style classically themed score to pounding techno, and the entire production slides into a kind of drug-fuelled gay-nightclub rave/delirium (this was my favourite part of the show). At the same time, the images on the screens – which have hitherto been in black-and-white, using dreamlike Expressionist or Surrealist-inspired dissolves and superimpositions that recall Rouben Mamoulian’s 1930s film version – explode into colour, invoking The Wizard of Oz (complete with footage of Backer as Dorothy and Leslie as the Cowardly Lion), while the two actors join hands and run off into the maze of screens, finally reappearing at the front of the stage wearing dresses and dance the can-can. We’re not in Kansas anymore.

A queer sub-text is certainly implied in Stevenson’s novella, but its narrative and thematic concerns lie elsewhere. Jekyll’s problem is one of compartmentalisation or splitting; the effect of the potion is to further dissociate the two aspects of his personality rather than reconciling them in a rainbow coalition of peace and love (it’s probably more like ice or crack than weed or LSD). His addiction to the drug (and the psychical fragmentation that results) facilitates the release of unchecked aggressivity and the death-drive, including the enactment of sadistic, destructive, misogynistic, homophobic, murderous and suicidal fantasies of domination and control over his victims (and ultimately himself). In this regard he arguably embodies the forces of right-wing reactionary populism or fascism more than sexual or political liberation.

Williams is less interested in Hyde’s more properly horrifying and monstrous attributes. Instead, the unspoken theme of queerness is heightened – especially in the final section, which almost feels like the raison d’être of the whole show. Consequently the allegory goes beyond the theme of duality – good and evil, Freudian ego and id, Jungian persona and shadow self – and becomes a prophetic celebration of contemporary theories and practices of multiplicity, non-binary ways of thinking and being, and even trans-identity. It’s a laudable aim, even if it feels like a bit of a stretch (I felt like Williams’s and Norvill’s gender-queering of Dorian Gray was closer to the mark).

For all the ingenious perversity of Williams’s adaptation and the razzle-dazzle, smoke-and-mirrors magic of his cine-theatre, the heart and soul of the production (as always) lies with the actors (as it did with Norvill in Dorian Gray). Backer’s Utterson conveys a touching vulnerability beneath his veneer of impassive stiffness and is wonderfully liberated when he finds his inner Dorothy in the final section. Leslie resembles John Barrymore in the silent film version both as Jekyll and when he transforms into Hyde with minimal changes in costume, makeup or special effects. While there’s a certain calculated and almost brittle coldness to his Jekyll – a quality which extends to all the other characters he plays, almost as if it were something inherent in the façade of Victorian masculinity itself – this is counterbalanced by his demonic Hyde, whose scuttling, cowering figure is dressed in a too-large overcoat and long, unkempt wig, and who addresses his interlocutors (and the camera) with glowering eyes, leering smile and rasping voice. Leslie manages to imbue this figure with the uncanny yet indefinable malevolence and repulsiveness required by the story (and which arguably exceeds the symbolic framework of Williams’s interpretation), while simultaneously embodying something abject and even pitiable, both monster and child.

All of this is captured and amplified by the astonishing video design and camerawork, especially by the team of Steadycam operators, who in one sequence chase the actors around the perimeter of the stage like paparazzi, while an expertly framed and (presumably) live-edited tracking shot follows them on the screens.

At times however I found myself longing for some relief from the predominantly mediated nature of my contact with the actors, as my eyes were continually drawn to the screens and away from was happening on the stage. It’s almost as if in cine-theatre ‘onstage’ has become a form of ‘backstage’ to which the audience is allowed access in the form of endless voyeuristic ‘sneak-peaks’.

Perhaps one could argue that in a Brechtian fashion the devices of cine-theatre expose the artifice of theatre and cinema – and potentially the hidden mechanics of capitalism and exploitation or the psychodynamics of repression and the unconscious – that normally occur ‘behind the scenes’. However, the effect is still predominantly to ‘cinematize’ the theatrical experience, framing everything for the benefit of the camera as a lure for the spectator’s gaze.

Clemence Williams’s thrilling but relentless score also emphasised the cinematic aspect of the show, imposing a hypnotic mood that risked becoming monotonous. The actors’ continuously rapid-fire delivery of non-stop text had a similarly relentless and hypnotic effect. This was exacerbated by their amplified voices being mixed into the soundtrack and dispersed around the auditorium with use of body-mics and surround-sound speakers, with the inevitable slight delay and echo that attends the use of live-feed audio and cinema-style sound equipment in a resonant theatre space. All of this made it hard for us to connect their voices to their bodies or to what was happening onstage (or even onscreen), or even at times to follow what they were saying.

In sum, I couldn't help feeling that there's a strange Jekyll-and-Hyde-like quality to the form of cine-theatre itself, with the cinematic elements devouring the theatrical ones, like a parasite devouring its host. At times I almost wished I could watch the two actors perform the show ‘unplugged’.

In a way, the whole cine-theatrical apparatus made me think of a hermetically sealed lab experiment, with the cine-stage as a space-time-compression chamber inducing a heightened version of what my friend and colleague the philosopher and architect Paul Virilio calls ‘speed-space’ – with the actors as experimental subjects, the adaptor-director and his fellow creatives as scientists, the crew as their assistants, and the audience as observers. Perhaps it’s a demonstration of the fact that we’re all Jekyll-and-Hydes now, addicted to the drug of digital technology, and trapped in our fragmented and compartmentalised performative identities and virtual worlds.

That said, it’s an amazing creation flawlessly executed, and the virtuoso performances by the actors and technical crew carry all before them. Williams is one of the most interesting directors working in theatre today; and Leslie is one of the most charismatic actors currently working onstage and onscreen.

*

Wolfgang von Flügelhorn is a writer and critic based in Perth, Western Australia. He was born and raised in Flügelhorn, a small town in Upper Austria, in 1963. After finishing his undergraduate studies at the University of Lower Flügelhorn he completed his doctoral thesis at Cambridge on the later Wittgenstein and the phenomenology of language games (Der später Wittgenstein und die Phänomenologie den Sprachspielen, unpublished) under the supervision of Wittgenstein’s literary executor Elizabeth Anscombe, whose famous paper ‘The First Person’ argues that the pronoun ‘I’ does not refer to anything. He left Austria and went into voluntary exile in 2000 after the formation of the far-right coalition federal government, vowing never to return. He is currently editor of the Zeitschrift für Unsozialforschung (Journal of Anti-Social Research) and Emeritus Professor at the University of Lower Flügelhorn where he holds a chair (remotely) in Paranormal Phenomenology while engaging his core muscles for two minutes every day. He is the author of several monographs including Unlogische Untersuchungen (Illogical Investigations), Unzeitlich Sein (Not Being On Time) and Wahnsinn und Methode (Madness and Method), all of which have been translated into English by his friend and colleague Humphrey Bower but none of which has yet been published in any language.

No comments:

Post a Comment